A strangely formless and insubstantial love-letter to Shakespeare

There is an vpstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers hart wrapt in a Players hyde_, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blanke verse as the best of you: and being an absolute_ Iohannes fac totum_, is in his owne conceit the onely Shake-scene in a countrey._

- Robert Greene; Greenes Groats-VVorth of witte, bought with a million of Repentance (1592)

"We know very little about the life of William Shakespeare." If you're ever reading something that says this, or any variation thereof, stop reading, and find something by someone who knows what they're talking about. Because the simple fact is that we know a great deal about the life of William Shakespeare. In fact, we know more about the life of William Shakespeare than we do about all of his contemporary dramatists and poets. Combined. There are, however, three areas where our information is sketchy. The first is that we don't really know anything about his personal opinion of the plays - did he have a favourite; were any of them personal for him; did he prefer comedy or tragedy, etc. The second is the so-called "Lost Years"; 1578-1582 (from leaving grammar school at 14 to marrying Anne Hathaway at 18) and 1585-1592 (from the baptism of his twins, Hamnet and Judith in Stratford-upon-Avon, to a contemptuous reference to him by Robert Greene in his tract Greenes Groats-VVorth of witte, bought with a million of Repentance as an up and coming dramatist who has already achieved considerable success in London). The third area for which we don't have a huge amount of information is the time from the burning down of the Globe Theatre on June 29, 1613 to Shakespeare's death on April 23, 1616.

And it is this later period explored by Kenneth Branagh (as director, producer, and star) in All Is True. A pleasant enough film obviously born from great reverence, and, unsurprisingly, brilliantly acted, it's a curiously formless piece of work, clumsily episodic in structure, and relatively free of conflict, focusing instead on non-incident and trees silhouetted against picturesque sunsets. By the very nature of the years during which it takes place, Ben Elton's screenplay is full of interpolations and suppositions, some of which are interesting, but many of which don't work. There's a much better film hidden in the contours of All Is True, a darker story examining Shakespeare's psychology; his inability to process the death of Hamnet, his guilt over the fact that he put his career ahead of his family, his possible misogyny, his obsession with his legacy. These issues are in the background, but they are not the focus, and whilst All Is True is perfectly fine, it's also perfectly forgettable.

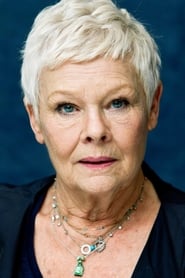

The film begins on June 29, 1613, as Shakespeare (Branagh) watches the Globe Theatre burn to the ground, after a canon misfired during a performance of All Is True (later renamed The Famous History of the Life of King Henry the Eight). Devastated by the loss of his theatre, Shakespeare decides to retire and return home to Stratford for the first time in 20 years (curiously, it is never mentioned that All Is True was most likely a collaboration with John Fletcher, or that The Two Noble Kinsmen, also written with Fletcher, was Shakespeare's last play). Coldly received by his wife Anne (a miscast Judi Dench; more on that in a moment) and youngest daughter, Judith (a superb Kathryn Wilder), he gets a slightly better welcome from his eldest, Susanna (Lydia Wilson). Still mourning the death of Hamnet (Sam Ellis), his only son, who died from plague aged 11 in 1596, Shakespeare decides to grow a garden to honour his memory. However, he must also try to deal with Judith's hatred for him, stemming from her conviction that he believes the wrong twin died, an accusation he seems reluctant to deny.

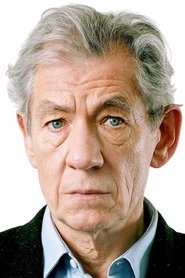

And that's about it as far as the plot goes, with everything else treated like a subplot – the animosity between Shakespeare and Susanna's devoutly Puritan husband John Hall (Hadley Fraser), a physician who believes every theatre in the country should be closed; Shakespeare's frustrations at having to deal with contemptuous local magistrate Thomas Lucy (Alex Macqueen at his smarmy best); Judith's reluctance to marry Tom Quiney (Jack Colgrave Hirst), a hard-drinking vintner with a reputation as a lady's man; accusations that Susanna is having an affair with the local haberdasher, Rafe Smith (John Dagleish); and Shakespeare's embarrassment that the sonnets he wrote for Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton (Ian McKellen) were published illegally, much to Anne's shame.

In terms of significant artistic output, Kenneth Branagh has few peers. The only person in history to have been nominated in five different Oscar categories, he has written and/or directed films such as the noir-homage mystery thriller Dead Again (1991), the irreverent "luvvie" comedy Peter's Friends (1992), the flawed but vastly ambitious Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1994), the scaled-back romantic comedy In the Bleak Midwinter (1995), the visually stunning but narratively weak musical The Magic Flute (2006), and the unpopular but aesthetically fascinating remake of Sleuth (2007). More recently, he has become an in-demand director-for-hire, working on such big-budget franchise films as (none of which I've seen) Thor (2011), Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit (2014), Cinderella (2015), and Murder on the Orient Express (2017), with Artemis Fowl and Death on the Nile both forthcoming. It could very well be the case that All Is True is a palette-cleanser, allowing him to return to the familiarity of Shakespeare, and work on a more intimate film after several years on relatively impersonal projects.

Of course, this is not his first filmic engagement with Shakespeare, and it is in his Shakespearean adaptations where, I believe, his real and lasting contribution to cinema can be seen - his extraordinary directorial debut, the savagely anti-war Henry V (1989), worth seeing just for his recitation of the "St. Crispin's Day" speech from IV.iii; the energetic and fun-loving Much Ado About Nothing (1993); the divisive 242-minute William Shakespeare's Hamlet (1996), audaciously filmed on 70mm; the box-office bomb that was his bizarre (but entertaining) musical adaptation of Love's Labour's Lost (2000); and the self-reflexive Japan-set As You Like It (2006). And this isn't even to mention his acting-only roles in film and on TV, his vast list of theatrical credits (which has seen him play Hamlet in no less than five different productions), his radio and audiobook work, and his appearance at Isles of Wonder, the opening ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics, where he played Isambard Kingdom Brunel reciting Caliban's "Be not afeard" speech from III.ii of The Tempest. I've seen a few people talk about how All Is True is the epilogue to Branagh's cinematic engagement with Shakespeare. I sincerely hope not, as we've yet to see him take on the unactable role yet.

The first thing to note about All Is True is how full of references it is to both Shakespeare's plays and incidents (or rumoured incidents) from his life. The idea that Shakespeare retired after the Globe fire is not original to the film, but was first hypothesised by Nicholas Rowe in Some Account of the Life of Mr. William Shakespear (1709), the first Shakespeare biography. Additionally, several of the subplots are taken from real life. For example, as the film shows, when a local man named John Lane (Sean Foley) accused Susanna of adultery, she and Hall sued for slander. When Lane failed to appear to provide evidence of his accusations, he was excommunicated, and Susanna was cleared. Also true is that in 1616, shortly after he married Judith, Quiney was charged with "carnal copulation" with Margaret Wheeler (Eleanor de Rohan), who had died in childbirth along with the baby. Admitting to the charge, he was fined five shillings, and Shakespeare altered his will so as to safeguard Judith's entitlements should Quiney attempt anything underhand; originally, the will had included a provision "vnto my sonne in L", but "sonne in L" was struck out, and Judith's name inserted. A third example is a running joke concerning the matrimonial bed. When Shakespeare returns to Stratford, Anne sees him more as a guest, and so assigns him the best bed, as was customary for visitors, whilst she takes the second-best bed. Over the course of the film, he continually tries to work his way back into her good graces (i.e. back into her bed). Famously, Shakespeare left Anne "my second best bed" in his will, which some scholars have read as an insult to her, whilst others have suggested the second-best bed was the matrimonial bed, and therefore of great symbolic significance. This is the position the film takes.

Elsewhere, there are references to The Merry Wives of Windsor (the composition of which Anne points out was what Shakespeare did to avoid dealing with the death of Hamnet); Macbeth ("I once uprooted an entire wood and moved it across a stage to Dunsinane"); The Winter's Tale (Shakespeare mentions that Ben Jonson "laughs at me because I speak no Greek and don't care whether Bohemia has a coast", an allusion to William Drummond of Hawthornden's assertion that Jonson mocked Shakespeare for giving the landlocked Bohemia a coastline in the play); the legend that Shakespeare fled Stratford some time prior to 1592 after he was caught poaching deer from Thomas Lucy's land (during an argument, Shakespeare tells Lucy, "I wish I had poached your bloody deer" - although, in reality, Lucy died in 1600); Robert Greene's contemptuous reference to Shakespeare as, amongst other things, an "upstart crow" (which Southampton chides him for still being bitter about); and Richard Burbage (Shakespeare refers to him as "a brilliant lunatic actor" who demanded "a bigger show for a smaller budget, and a shorter play with a much longer part for himself"). There's even a subtle reference to the ridiculous Shakespeare authorship question, when Henry (Phil Dunster), a Cambridge student, travels to Stratford to ask Shakespeare how he knew "everything", pointing out, "there is no corner of this world which you have not explored. No geography of the soul you cannot navigate. How? How do you know?" I'm also fairly sure Branagh quotes himself at one point; arriving back at Stratford, a shot from inside the Shakespeare house shows the door opening and Shakespeare standing in the doorway, heavily silhouetted against the light outside, which is exactly how we first see Henry in Branagh's Henry V, silhouetted in a doorway.

A particularly funny reference concerns Titus Andronicus. When trying to scare Lane out of testifying against Susanna, Shakespeare tells him about the Moorish actor who played Aaron, a man "magnificent and terrifying. Mighty like a lion. Strong as a bear. I saw this man tear the heart from a fool who wronged him and eat it raw!" Explaining that the man is in love with Susanna, and would do anything for her, even though he knows they can never be together, Shakespeare tells Lane, "he swore that if ever she had need, his sword, his claws and his teeth would either defend her or kill for her. Should I tell him of Susanna's current distress?" This is intercut with an African-American actor (Nonso Anozie) reciting Aaron's menacing last speech from V.i, in which he brags about his life of misdeeds. However, when Shakespeare tells Anne, she confusedly reminds him that she met the actor who played Aaron, and "he was the sweetest chap you should hope to meet", to which Shakespeare acknowledges, "yes he was, lovely fellow".

A critical scene, and easily the best in the film, involves Southampton visiting Stratford. Excitedly telling Anne of the impending visit, she rebukes him, reminding him that a lot of the town's folk read the poems, to which he replies, "those sonnets were published illegally. Without my knowledge or consent". Later, speaking to Southampton, Shakespeare states,

they were only meant for you, Your Grace. Not for any other living soul nor any yet to live. Just you.

This alludes to the theory, popular during the nineteenth century, though somewhat out of favour now, that the original publisher of the sonnets, Thomas Thorpe, did so without Shakespeare's consent. The film also addresses the question of the identity of the "fair youth" to whom the first 126 poems are addressed. Often assumed to be one and the same as the dedicatee, "Mr. W.H.", ("To the onlie begetter of these insving sonnets Mr.w.h. All happinesse And that eternitie Promised By Ovr ever-living poet Wisheth The well-wishing Adventvrer in Setting forth"), the two main (but by no means only) theories as to his identity are Southampton and William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke. Pembroke was Shakespeare's patron and one of the dedicatees of the First Folio in 1623. Additionally, one of the primary motifs of the first 17 sonnets (the so-called "Procreation sonnets") is an attempt to convince the youth to marry, and in 1595, when many of the poems were written, Pembroke was being urged to marry Elizabeth Carey, which he refused to do. Southampton, on the other hand, was the dedicatee of Shakespeare's earlier narrative poems Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece, and was well-known for his good looks.

In the film, there is little room for doubt - Southampton is the fair youth. When he points out, "it was only flattery of course", Shakespeare responds, "just flattery. Except, I spoke from deep within my heart", which Southampton dismisses with, "well, I was younger then. Younger and prettier". Shakespeare then quotes in its entirety "Sonnet 29" ("When in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes"), with Branagh reading it as an agonised ode to an impossible love. He then alludes to the fact he'd always hoped Southampton may have one day reciprocated his love, to which Southampton reacts sternly, telling him, "y_ou forget yourself, Will. As a poet, you have no equal. And I, like anyone with brain and heart am your humble servant. But as a man, Will, it is not your place to love me_". Getting up to leave, Southampton then also recites "Sonnet 29", with McKellen's intonation changing it into a celebration of the power of art to transcend such foolish distractions as love. It's a beautifully shot, incredibly well-acted, and deeply nuanced scene that, if it accomplishes nothing, serves to remind us just what talented actors can do when reciting the exact same text, simply by modulating their tone.

One of the film's main themes is, of course, family, with Elton's script focusing on how resentful Anne and especially Judith have become of Shakespeare. We don't know a great deal about the real Judith, so much of Elton's characterisation is speculative. The film's Judith is essentially a protofeminist, a brilliant, complex, and acerbic woman railing against the narrow-minded patriarchy her father endorses, boldly telling him, "nothing is ever true". The likelihood of this being the case is slim at best, but Wilder is excellent in the part and makes Judith much more believable than the character has any right to be. Where Elton is more successful, and on firmer factual ground, is that Shakespeare's interest in his daughters' marriages revolves primarily (if not exclusively) around whether they can give him male grandchildren, now that Hamnet can't carry on the family name. The film acknowledges that Shakespeare was a neglectful father and husband, and never fully gets behind him as he defends himself by citing the cultivation of his genius, pointing out that his talents made the family very wealthy, and thus he should be excused. However, by the end, even he doesn't believe this himself, coming to understand the price his family paid for his greatness.

Aesthetically, cinematographer Zac Nicholson (The Death of Stalin; The Guernsey Literary & Potato Peel Pie Society; Red Joan) seems to have watched one too many Terrence Malick movies during preproduction, but as with everything Branagh directs, there's a sincerity and verisimilitude to the visual design. Nicholson's interior compositions draw inspiration from various Baroque painters, with the daytime scenes recalling Gabriël Metsu and Johannes Vermeer, and the nighttime scenes drawn from the likes of Michelangelo da Caravaggio and Georges de La Tour. His exteriors, as one would expect given the similarity to Malick, are from German Romantics such as Joseph Anton Koch, Caspar David Friedrich, and Carl Blechen. The nighttime compositions are particularly striking, often lit with only practical candles, making use of shallow focus and strong contrast as characters huddle together in narrow shafts of light. Adding to the effect is the excellent production design by James Merifield (The Deep Blue Sea; A Little Chaos; Mortdecai) and Branagh's unexpected, but not unwelcome, use of gentle Dutch angles to underscore moments of heightened tension.

However, there are some considerable problems. First and foremost is the script, which has a strangely formless structure, derived from an extremely episodic organisational principal, with scene after scene addressing one and only one issue at a time, ensuring each issue is cleared before moving onto the next. The accusation against Susanna, for example, is introduced, developed, peaks, and resolves in around 15 minutes, dutifully followed by the next subject, which repeats the pattern. Scenes often involve the characters saying only what is necessary to get to the next scene, with little room to breathe, almost as if we're watching a "previously on" montage of a TV show. Because of this, when we do get scenes that are given a bit of time, such as the Southampton scene, they stick out, stylistically detached from the surrounding material. Additionally, what should have formed the core of the story, the allegations against Susanna or the question of Judith's marriage, for example, are instead treated like subplots. The problem with this is that because the main plot has a distinct lack of urgency, and is relatively conflict-free, the subplots come across as much more vital, only for them to be constantly interrupted by the less engaging main narrative.

Another issue with the script is its use of 21st-century gender politics. This kind of retconning, of course, is nothing new, and the question the film raises is an interesting one - was Shakespeare so ensconced in patriarchal thinking that the lack of a male heir blinded him to the fact that one of his daughters may have had the ability to carry on his poetic legacy, if not his name. Maybe he was, I don't know. None of us know. But the film's answer is the worst type of filmic oversimplification. Every woman around Shakespeare is a protofeminist, each of them more progressive (in the modern sense of the term) than him. And thus, the film builds to the moment when he comes to see they were right all along, scolding himself for his short-sightedness and boldly embracing the idea of gender equality. It's a poor attempt to graft contemporary ideology onto an epoch that simply had different beliefs. It's one thing to say Shakespeare may have been in been in favour of the female parts being played by women. It's one thing to say that The Taming of the Shrew may have been written to satirise and mock misogynistic attitudes rather than endorse them. It's something else entirely to say that Shakespeare, by the end of his life, was a feminist, and would eagerly have burnt his bra, given the chance. That takes speculation into the realm of the incongruous, as if Elton and Branagh are afraid to judge him by any standards other than their own.

The casting is also problematic. Now, don't get me wrong, I love Dench and McKellen as much as the next man, and they're both excellent in the film, but that doesn't change the fact that they are both badly miscast. Both play their characters as elderly, but in 1613-1616, Anne (played by the 84-year-old Dench) was 57-60, and Southampton (played by the 79-year-old McKellen) was only 40-43. Additionally, Anne was six years older than Shakespeare, but Dench is 26 years older than Branagh, and it shows. And whilst age discrepancies can often produce fascinating results (in Laurence Olivier's Hamlet (1948), for example, the actress playing Hamlet's mother Gertrude (Eileen Herlie) was 11 years younger than Olivier himself), here it just distracts from the content.

As a massive Kenneth Branagh fan (and a fan of Ben Elton's wonderfully irreverent comedy Upstart Crow), I was pretty disappointed with All Is True. Equal parts sullen and playful, Branagh's Shakespeare is both an extraordinary genius, not of the ilk of everyday mundanity, and a man who lives in the world and must deal with its absurdities. The film tries to strike a balance between a laid-back and wistful story about a retired writer, and a study of filial grief, with the dawning realisation that much of that grief could have been avoided. Some elements unquestionably work; the Southampton scene, Shakespeare's struggle to reconcile his one-of-kind genius with the personal cost of that genius for both himself and others, Judith's resentment of Hamnet, the night-time photography, the humour, the myriad of references. But a hell of a lot doesn't work. It's an inoffensive and perfectly fine film, but given the director and the subject, it could, and should, have been so much more.